The public sector’s greatest risk is mistaking compliance for capability

As Australia's federal agencies move from owning systems to governing intelligence, vendors must deliver data readiness and trusted AI.

As Australia’s federal agencies move from owning systems to governing intelligence, vendors must deliver data readiness and trusted AI.

Australia’s public sector is entering a decisive moment.

The work of modernisation used to revolve around system ownership, capital investment, and compliance targets.

At Government Edge, a different understanding surfaced.

Senior government executives revealed that the real contest ahead will centre on who governs intelligence with the most confidence.

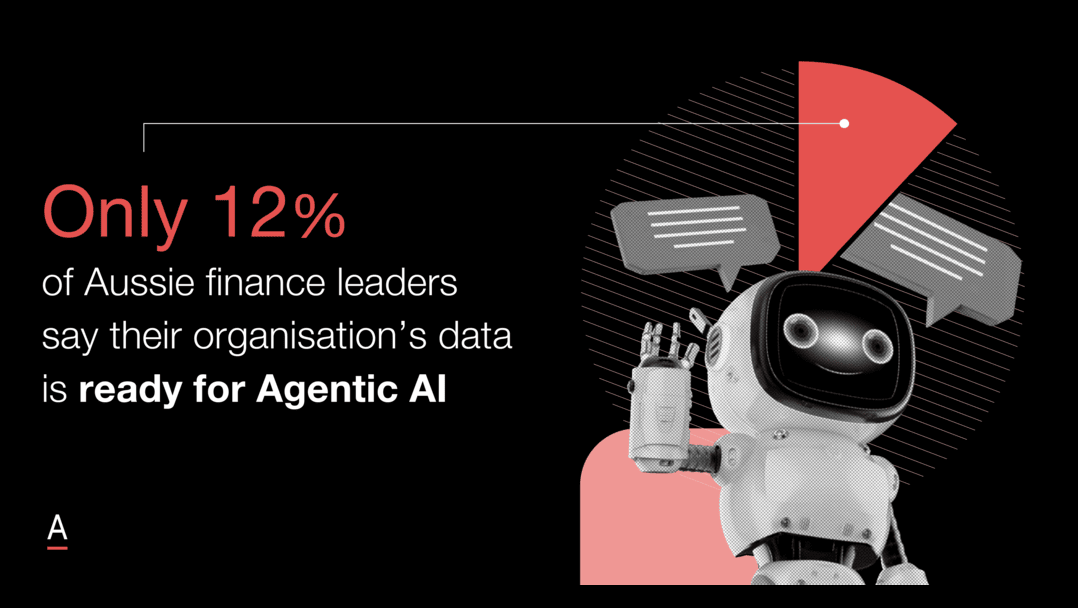

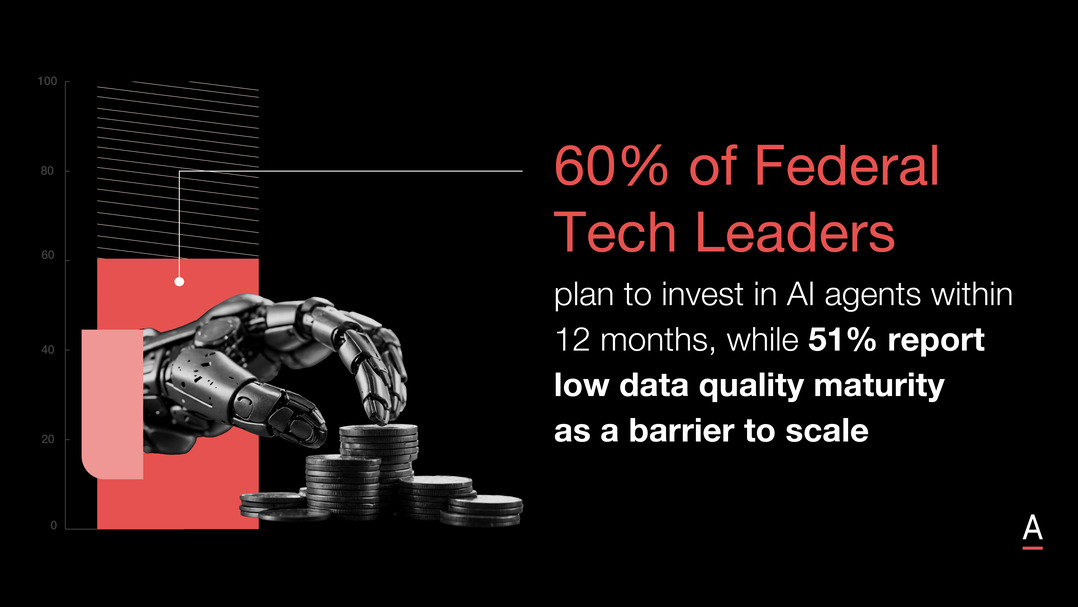

Agencies want to invest in AI at scale, yet many lack the foundations to govern, explain, and secure those systems.

ADAPT’s research reflects this tension. 60% of agencies intend to increase AI investment, but 52% remain below Level 2 maturity on the Essential Eight controls.

This signals ambition rising faster than institutional capability.

Agencies want partners who can strengthen visibility, accountability, and assurance within intelligent systems.

Sovereignty will belong to those who can govern intelligence, not own the infrastructure

Historically, sovereignty referred to location where infrastructure lived inside national borders. Control was physical.

The conversations at Government Edge showed how fast this idea is changing.

Sovereignty now expresses itself through control of data, decision paths, and algorithmic integrity.

The location of the platform matters far less than the authority governing it.

Chris Crozier, Chief Information Officer and Deputy Secretary at Defence Digital Group of the Department of Defence, captured this shift with clarity.

Defence uses global hyperscalers, yet control rests firmly with teams who hold the keys, identity systems, access rules, and data protections.

Sovereignty therefore becomes a posture shaped by oversight rather than hardware presence.

It is a model that accepts global capability while protecting national authority.

This same principle shaped Mark Sawade’s contribution.

The Chief Information Officer at the Australian Taxation Office described sovereignty as a balancing act between innovation and accountability.

He showed how value for money, risk management, and local oversight determine which services should be built domestically and which can be drawn from global ecosystems.

For him, sovereignty strengthens when agencies understand where each lever of control truly sits.

Radi Kovacevic, Chief Digital Officer at the Department of Home Affairs, drew attention to the tension created by strict data residency and the realities of modern AI.

Hus teams operate within rules that keep sensitive data onshore while engaging with models trained on global corpora.

This requires an advanced form of governance, one that assesses the behaviour of systems trained elsewhere but executed under Australian constraint.

Judy Hurditch, Managing Director and Principal Analyst at Intermedium, added a long view of spending patterns.

Her analysis showed cloud contracting rising toward $2 billion in 2025, even as budgets tighten.

This underscores how agencies accept global infrastructure while demanding far more control over its behaviour.

Sovereignty is now a technical discipline driven by transparency, auditability, and evidence of trustworthiness.

This trend is reinforced by data. 42% of public sector leaders cite sovereignty and control as the main barrier to AI adoption.

For vendors, this marks a strategic reframing.

The most valuable partners will be those who enable algorithmic sovereignty through clear visibility into systems, reliable audit trails, and accountability kept inside Australian borders.

As agencies reexamine tech strategy through this lens, sovereignty becomes the first chapter of a broader story.

That story continues as agencies confront a second pressure shaping their decisions: the reality of shrinking budgets and rising expectations for intelligence.

The winners will be those who turn shrinking budgets into smarter intelligence

Sovereignty leads directly into a more practical concern. Agencies face the lowest ICT funding in a decade while expectations for intelligence, insight, and automation rise sharply.

This environment forces leaders to rethink how value is created.

Rather than expanding infrastructure, they are strengthening the capability of existing systems to generate intelligence that improves service quality and supports reliable decision making.

This theme emerged strongly in Judy Hurditch’s assessment of the funding landscape.

Capital projects are being scrutinised more heavily, while cloud spend continues to rise.

Agencies are buying fewer large systems and shifting toward contracting that enables clarity and control.

They want environments that reduce complexity, strengthen governance, and support decision intelligence without exceeding budget constraints.

Charles McHardie AM, Chief Information and Digital Officer at Services Australia, demonstrated what this evolution looks like in practice.

His organisation advances modernisation through modular improvement of existing architecture.

Each change strengthens stability and delivery discipline so that new intelligence capabilities land on dependable foundations.

He sees improvement as an ongoing cycle rather than a program that resets the environment every few years.

Nicholas Flood, Managing Director ANZ at IBM added that modular modernisation increases resilience by distributing transformation across smaller, controlled stages.

This approach preserves service continuity for millions of Australians while giving agencies the flexibility to introduce intelligence at a pace the institution can manage.

Insight becomes an outcome of careful sequencing, not radical overhaul.

In an interview with ADAPT, Michael Harrison, Chief Information Officer at the Attorney-General’s Department, demonstrated the connection between intelligence and governance by describing how his department achieved sustained Essential Eight maturity.

The uplift came from consistent governance improvements rather than capital-intensive technology refreshes.

The lesson is straightforward. Intelligence maturity emerges when the rules, routines, and accountability structures evolve, not only when platforms change.

This aligns with ADAPT’s research. 68% of government leaders now prioritise simplifying legacy infrastructure and data environments to support AI-driven decision making.

Agencies want systems that can be governed, monitored, and understood.

Vendors who respond to this need will shift from selling expansion to enabling coherence.

The next competitive advantage comes from helping agencies convert shrinking budgets into smarter intelligence.

This emphasis on intelligence then leads to the question that threads through every agency conversation: can these systems be trusted under public scrutiny?

Trust will decide who shapes the future of public sector AI

If sovereignty defines the boundaries and intelligence defines performance, trust defines legitimacy.

Leaders across the public sector are clear that trust will determine whether AI reaches scale.

The pressure on agencies is immense.

Citizens expect fairness, transparency, and accountability. Executives expect reliability.

Teams expect systems that protect their judgment, not replace it.

Vendors must support all three expectations through design that reveals how decisions are made.

Nick Herbert, Executive Director, Global Public Sector at ServiceNow, described four groups that shape trust in government AI.

Leaders focus on strategic clarity. Users prioritise reliability and smooth experience. Citizens look for fairness and explanations.

Leaders focus on strategic clarity. Users prioritise reliability and smooth experience. Citizens look for fairness and explanations.

Builders concentrate on safety, data quality, and guardrails. Trust emerges when systems meet the needs of all four groups simultaneously, and failure in any group weakens adoption.

Nicholas Fletcher, AI practice, QuantumBlack at McKinsey & Company, extended this idea by examining the Gen AI paradox.

80% of organisations deploy AI but only 20% see tangible value. He argued that the gap has little to do with model capability and everything to do with governance.

Systems gain power faster than institutions gain discipline, and agencies hesitate to expand capability until those controls mature.

Professor Marek Kowalkiewicz, Professor and Chair in Digital Economy at Centre for Future Enterprise, QUT Business School, called on government leaders to adopt a new form of stewardship.

He argued that public servants must govern intelligent systems with intentional oversight.

This includes active monitoring for fairness and impact, clear accountability structures, and boards and executives who understand the implications of algorithmic decision making.

As systems act with greater autonomy, institutions must respond with greater clarity. Data reinforces the urgency.

60% of government CIOs expect to pilot or scale AI by FY26, but fewer than 20% have agency-wide governance frameworks.

Vendors must therefore treat trust as an operational requirement.

Explainability, transparency, and human oversight need to be built into systems from the beginning.

Agencies will only scale AI where trust is proven rather than promised.

As sovereignty pressures shape the boundaries and budget constraints shape the priorities, trust now dictates which vendors will influence the next chapter of public sector modernisation.

Recommended actions for technology vendors

Technology vendors working with the public sector will help shape national capability if they build for intelligence governance rather than infrastructure expansion.

The following principles capture where government is heading and what vendors must enable.

- Support algorithmic sovereignty – Design systems that provide clear audit trails, expose decision paths, and keep accountability inside Australia. Agencies want confidence that they can explain and verify outcomes.

- Enable intelligence maturity within constrained budgets – Help agencies simplify data structures, automate governance processes, and unlock insight from existing environments. Proposals must show how intelligence improves, not how systems grow.

- Build trust into every layer of design – Provide transparency, fairness testing, model assessment tools, and reliable oversight mechanisms. Produce evidence of consistency across environments.

Trust becomes an operational asset when it is measurable.

Capability in transparency, control, and accountability will replace hardware scale as the measure of value.

Agencies will reward vendors who help them govern intelligent systems with confidence.

Progress will be measured by how intelligently institutions govern, not by how many systems they own.