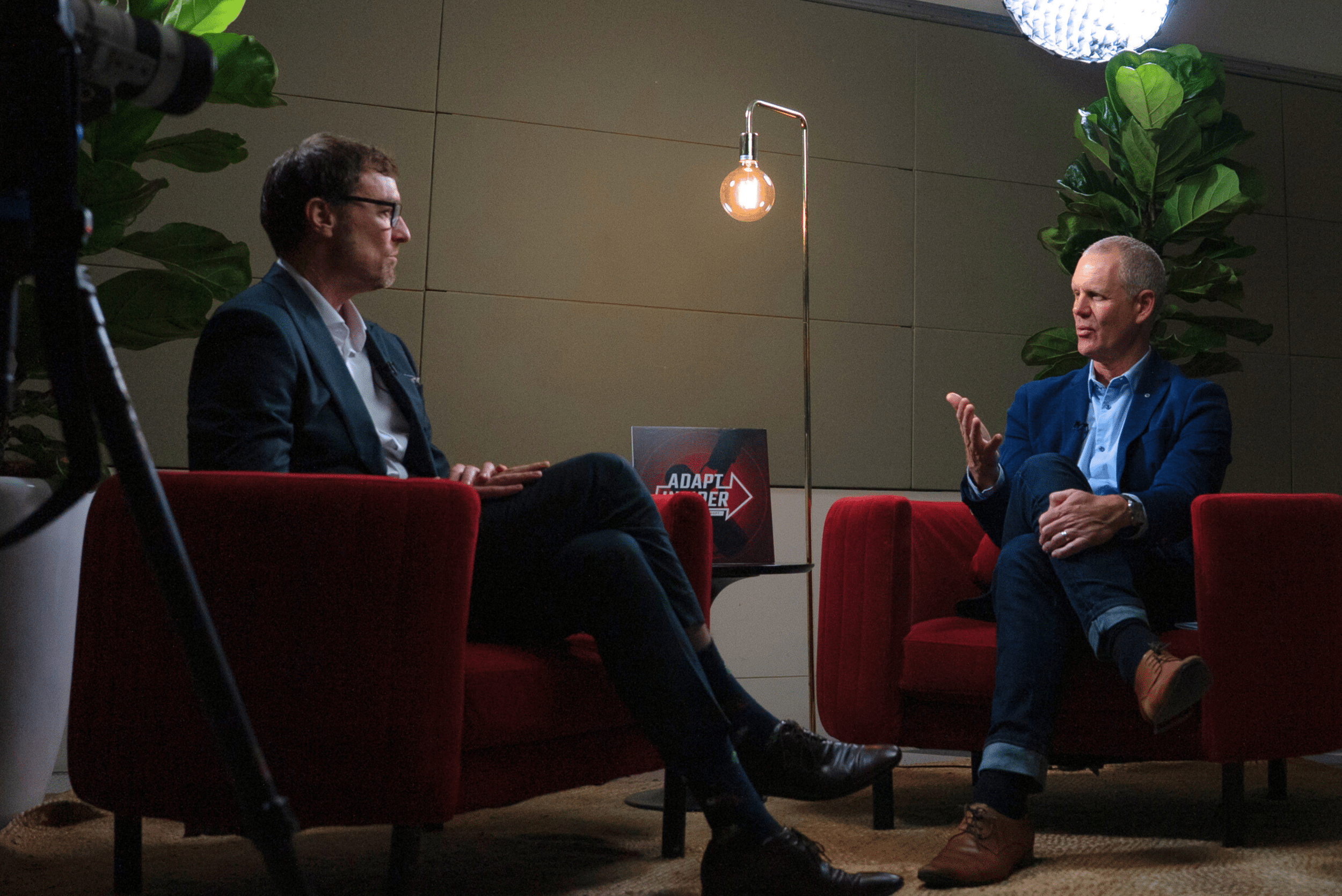

Dr Ian Oppermann is NSW Government’s Chief Data Scientist, overseeing exabytes of customer data within the Department of Customer Service.

Ian is Australia’s chief proponent of effectively utilising data in the public sector and a tireless advocate of generating meaningful insights from data.

Speaking at ADAPT’s Digital Edge Senior Analyst Peter Hind, Ian discusses the shortage of Australian data scientists. Both universities and vocational training institutions will play a critical role in filling the current skills gap.

At NSW Government, Ian is recruiting students with a Master of Data Science from the University of Technology Sydney. He explains how these mature-aged students have a diverse perspective on effectively leveraging data, which is just as important as technical proficiency.

Ian also explores how the many executive owners of data governance must address earlier input and long-term, data-driven decision-making.

When asked how to face the never-ending challenge of data cleansing, he spoke about the critical role automation and profiling tools have to play.

Peter Hind:

Everyone says we’re drowning in data, there’s a tsunami of data. We’ve got devices like the Internet of Things that will create even more data.

How do we get the data scientists who can start to interrogate and interpret this data? We’re hearing from everywhere around the world there’s a dearth of data scientists, the universities aren’t turning them out.

How do you suggest organisations go about developing their data assignments?

Ian Oppermann:

That’s a great multi-problem question. The first part about the data is just a little throwaway effect. We tried doing it back the envelope calculation as to how much data New South Wales Government has.

We very critically came up with exabytes and in fact fractions of a zettabyte. That’s a pretty serious amount of data, not all of which is being used.”

We’ve been very fortunate in that the challenges we look at are those wicked policy challenges that are complex and subtle and ultimately have people’s behaviour at their heart, it’s really easy to find people who want to change the world, to find people who want to drive positive outcomes.

But more broadly, there is a real challenge, I believe, with the quality and the range of data scientists.

The best data scientist is not someone who’s just got a degree in or understands Python, or understands JSON, it’s someone who actually has lived and has experienced the world.”

Because ultimately, data science is not something in its own right, Whether it’s in the commercial world or government world, it affects the way we live.

There were some great improvements in the types of tools and just how much of the process of data science from finding the data to cleansing it to prepping it to analysing it. Those tools are getting more integrated, the scope is increasing.

That’s helping a great deal and making our data scientists more productive, but without real focus from the education system.”

That does not only include universities, but also vocational training. Without greater uplift in the emphasis on data analytics, I think we’re going to struggle for a while longer.

Peter Hind:

You’re talking about the value of evolving people into a data scientist role. We’ve got to have world experience so they can bring some interpretation to that, which is important.

Ian Oppermann:

We’ve had a great partnership with the University of Technology, Sydney which is within walking distance from the office.

We have been over the last almost four years taking their Master of Data Science students who all come in as mature students who have been lawyers or have been having a technical background or have a communications background. These people are absolute gold.

Peter Hind:

There’s increasing obligations on organisations regarding data breaches, privacy obligations to respect or guard the data they possess in law organisations. What are your thoughts about data governance and people taking ownership of the data that their organisation possesses?

Ian Oppermann:

One of the points about data governance is that there are so many steps in the chain, that it doesn’t belong to one person, there’s an educational requirement for everybody. That governance really starts even further and earlier than we think.”

We’re starting to think about the sources of data, not the first time you take it into your organisation but where the data comes from.

What we choose to actually measure data from what we choose to see through the lens of data, all the way through to the more traditional governance process associated with the project, right through to what you might call the exhaust process. What do we do with it after we finished after we’ve analyzed and got our insights out of it?

It is a much more comprehensive problem than I think we have thought of tonight. It relates to what happens to the outputs and the insights themselves.

Tools are helping with that basic core of data governance, but the unfolded parts of governance really relate to much early input.”

What do we do with results in the long term? What do we do with the consequences of those results in the long term?

Peter Hind:

Given the volume of data that’s coming in and what organisations are acquiring, is it feasible to really do data cleansing with that volume of data?

If you’re not doing data cleansing, are you then making decisions on data that’s been polluted?

Ian Oppermann:

This is another big hairy problem, We have always had a lot of students and every student, every intern has to do data cleansing, to begin with, it’s the rite of passage.

You don’t get to touch the data until you’ve done your time doing data cleansing.”

That has a short term benefit for us. We can give also back to agencies better quality data.

When the projects are finished, we can say this is the value of having better data. There is no one group who can take responsibility for data cleansing, it’s something that everybody has to see we’re investing in. There are tools that are helping better characterise and profile data. It’s an ongoing battle.

The data tide is coming in very fast and we’re paddling like crazy to try and stay ahead of it. I’m not sure who’s going to win.”

But the good thing is that we are certainly producing streams that have better quality data that we know we can use for more and more purposes.

As that data quality improves towards the 99.99, whatever your number of nines is, certainly we can use it for more things and create more value, which will have a positive reinforcement cycle. But the tide is coming in quickly.

Peter Hind:

Okay, you’re implying in some ways that there is always a laborious side to data cleansing, but maybe tools and automation and things like that may simplify the task.

Ian Oppermann:

That’s why there are some good profiling tools. And there are some great ways of taking reasonable quality data and improving it, push it up another nine or so.

But there’s always the temptation when you get a result you don’t quite expect to go back and look at the raw data.

Human being eyeballing is a very slow process that can be a very insightful process. But whilst there’s an element of that, it’s going to be a very non-scalable activity.